Tribute to Dr. Charles H. Long

Without Understanding the Africans in the Atlantic World, You Cannot Have a Clear Understanding of What the Modern World Is ~ Dr. Charles H. Long, Historian of Religions

Essay by Dr. Sheila S. Walker

The African Diaspora and the Modern World was the title of the 1996 conference I organized, with support from UNESCO, at the University of Texas at Austin when I was Director of the Center for African and African American Studies. The conference, to which I invited more than sixty people from more than twenty countries in Africa, the Americas, and Europe, differed from most academic gatherings by including non-scholars.

I invited as presenters representatives of Afrodescendent communities both little-known and often denied, such as Argentina and Uruguay, and well-known and undeniable, such as Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia. Speaking for themselves and telling their own stories were cultural and community leaders who had been my teachers and had shared their realities with me, rather than the usual outsider researchers who studied these people, claimed to represent them, and spoke about and for them—but did not create opportunities for them to speak for themselves.

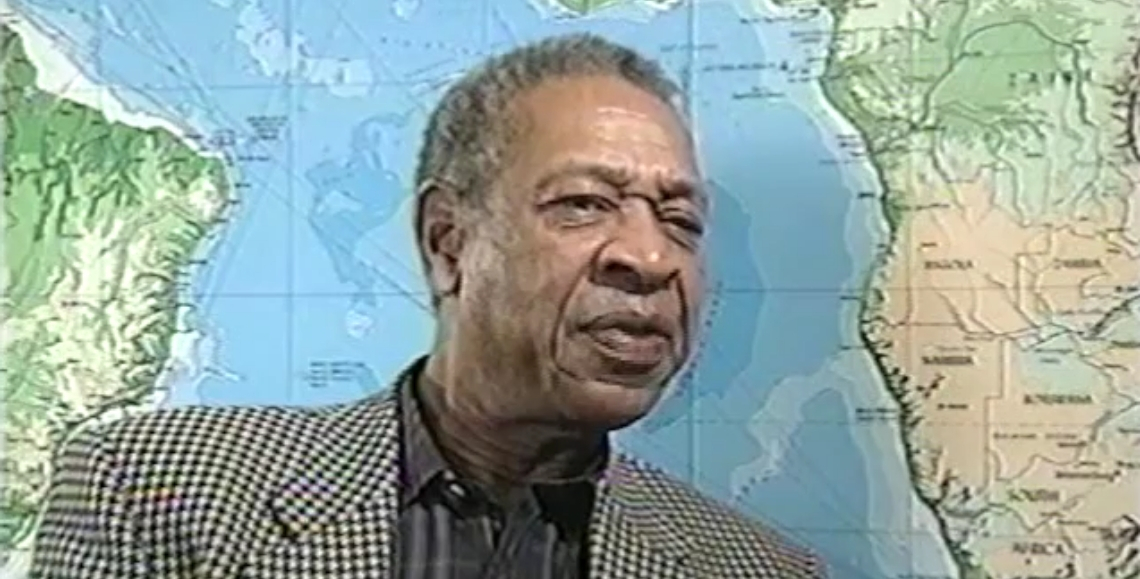

I invited to give the keynote address Historian of Religions Dr. Charles H. Long. He had been my favorite and most enlightening professor at the University of Chicago, the sine qua non of my surviving graduate studies in Cultural Anthropology, and the major supporter of my research, publishing, and academic career. Charles Long provided a conceptual foundation for the theme of the conference and an explanatory framework for understanding the larger implications of the presentations.

The following video clips of Dr. Long are highlights from my documentary, Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora, which was filmed at the conference. The full videos of his keynote and of an interview with him are on the conference page. To watch the clips, click each video’s play button.

Long’s assertions about the seminal role of Africans and their descendants in the creation of the Atlantic and Modern Worlds, along with conference discussions of the systemic racism that has obscured and distorted both this reality and knowledge of this reality, reflect current concerns.

The combination in 2020 of the massive national and international reactions to the grotesque public murder of George Floyd by state-sanctioned “forces of order,” coupled with the disproportionate illness and death tolls from COVID-19 of Black people in the United States, has led to an examination of the meaning of the presence and roles of African Americans, and provoked similar examinations concerning African and African descendant presences elsewhere in the Atlantic World. Demonstrators in France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and other countries protested discrimination against and killings of Black people. They all insisted that Black Lives Matter. As in the United States, demonstrators also tore down statues celebrating enslavers and colonizers and called into question the inhumane processes for which these men were responsible, and for which they were honored.

I produced Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora, featuring African and African descendent scholars and cultural and community leaders, to make accessible the knowledge and perspectives shared at the conference. I would have thought the documentary, originally produced in 2001 and re-edited in 2017, which I showed in many educational and cultural venues nationally and internationally, would be obsolete by now. I hoped the truths contained in it would have become common knowledge. That has not happened. The documentary continues to surprise viewers two decades later with information of which they are absolutely unaware, information basic for understanding the history and present of the Americas and the Atlantic World.

In what became the modern Americas of the last five hundred years, a new people was born in and into this Indigenous territory that was conquered and colonized by Europe. Africans enslaved by Europeans, transformed into Afrodescendants after surviving the horrible trans-Atlantic voyage, participated in creating a “New World” that became new in large part because of their presence and contributions. They developed this land through generations of unremunerated labor and enriched it with African technological expertise and cultural knowledge. In doing so, they in myriad ways indelibly marked it as their new homeland.

Whereas many of these ways remain to be researched, acknowledged, and properly attributed, many others were discussed at the conference and elaborated in the volume, African Roots/American Cultures: Africa in the Creation of the Americas, that resulted from it.² For example, economic historian Joseph Inikori wrote of how the Industrial Revolution was fueled by the unpaid labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants; dance scholar Brenda Dixon-Gottschild wrote of African and Afrodescendent movement vocabularies found in Euro-American concert dance; and Mario Luis Lopez and Lucia Dominga Molina wrote of contributions to Argentina of the Africans and Afro-Argentinians whose existence the country has denied, although its national dance has the Central African Bantu name—Tango.

In Scattered Africa, Howard Dodson, then Chief of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, reinforced with demographic data Long’s claims about the centrality of the African presence in the Modern World and insisted on scholars’ responsibility to tell the truths of the Americas.

These calls for an honest consideration of the influence of Africans and their descendants in the making of the Modern World involve acknowledging the motives and counteracting the mechanisms of Eurocentric demeaning of these groups. The resulting ignorance of their accomplishments and contributions was engineered to justify the enslaving of Africans and the continuing oppression of Afrodescendants. A lack of knowledge of the importance of their own history leads some U.S. African Americans to embrace a limited and limiting identity.

Charles H. Long:³ “This is important for African Americans. First, so they will not have a false sense of who they are, and second, so they can know the modes by which other Africans in the Americas figured out and understood their lives. They need to be in communication with them to have a sense of a much wider world and a deeper world of meaning.”

Charles H. Long: “At this conference, we are in so many ways allowing the facts to speak for themselves, and out of that are beginning to see the beauty, the truth, the openness of this African world in the Americas. People of African descent must take our freedom from the resources we have, and part of that arsenal is our Africanity. Africa was never forgotten. So over these hundreds of years, being in Africa while being away from Africa was a lived reality.”

Charles H. Long: “We have retained whatever understanding or memory we have of Africa, not just as a relic, but as a useful meaning of how we cope with the world. We have used Africa as a creative mode of maintaining ourselves in an alien land. So part of being an African of the Diaspora meant that we were always going back to Africa, even when we stayed in the same place. We never stopped being Africans.”

These dancers, who illustrate so well Long’s words to music played by Cameroonian Georges Collinet, are from different North and South American nations, had never danced together, and had never heard the Central African tune to which they were dancing. Yet they “recognized the beat.”

Long concludes with an observation—and a challenge.

NOTES:

¹ Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora, 2001, Afrodiaspora, Inc., 2017.

² Walker, Sheila S. Editor, African Roots/American Cultures: Africa in the Creation of the Americas. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2001.

³ These quotations from Charles Long are from the same interview as the video clips shown here.